They have up to 21 arms, hundreds of toxin-tipped thorns, a taste for coral, and can occur in plague proportions. No wonder crown-of-thorns starfish have a formidable reputation on the Great Barrier Reef.

Outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish are responsible for extensive loss of reef-building corals on the Great Barrier Reef and elsewhere. Scientists and managers work together to understand outbreaks and develop new ways to control them.

About this spiky, toxic coral eater

Crown-of-thorns starfish are large marine invertebrates which feed on coral as adults. The starfish, often referred to as COTS, are native to the Great Barrier Reef, and not an introduced species. They occur naturally throughout the Indo-Pacific region, on coral reefs from the Red Sea to the west coast of the Americas.

Genetic studies show there are at least four species of crown-of-thorns starfish. These are the North and South Indian Ocean species (Acanthaster planci and Acanthaster mauritiensis), a Red Sea species (not yet named) and a Pacific species. The latter is found on the Great Barrier Reef and is currently referred to as Acanthaster. cf. solaris.

The starfish can grow up to 80 cm in diameter. Despite their large adult size, they are often difficult to find on a reef, preferring to hide under ledges or in reef nooks and crannies.

An appetite for reef-building corals

Adult crown-of-thorns starfish have an enormous appetite for eating hard coral. An adult crown-of-thorns starfish can consume up to 10 m2 of coral a year. Like other starfish, they feed by pushing their stomach out through their mouth, covering their coral prey with digestive enzymes and converting coral tissue into a coral soup. When finished feeding they simply retract their stomach back into their body.

Adult starfish generally prefer to feast on fast-growing corals, such as branching corals and plate corals of the genus Acropora.

A huge capacity to reproduce

Crown-of-thorns starfish breed through spawning over the summer months. Females and males will release their eggs and sperm into the water at the same time to fertilise.

Did you know? A large female crown-of-thorns starfish can release over 200 million eggs a year!

The resulting starfish larvae drift as plankton for 10-30 days where they feed on microscopic plants called phytoplankton.

When ready, they begin their life on the reef by metamorphosing from larvae to a distinct but small starfish form with five arms.

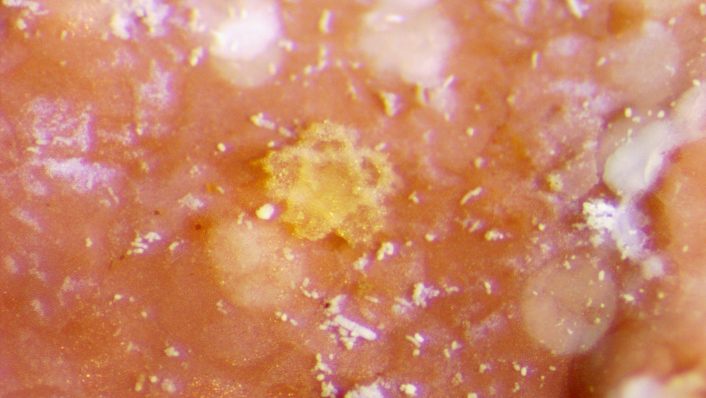

Juvenile starfish are cryptic (meaning they are difficult to find), and feed mostly on crustose coralline algae, types of hard algae which form a pink crust across all reefs. Within six months to a year, a juvenile starfish will change again into its adult form and begin eating coral.

Within two years, the starfish can be mature, and start to reproduce.

Spines and slime defend against predators – but not all

The crown-of-thorns starfish gets its name from the numerous sharp spines that cover its upper body. These spines are up to 4cm long and are effective in deterring many would-be predators.

To combat those predators brave enough to attack, the starfish have another line of defence - a toxic slime. Their spines are covered in plancitoxins which can cause liver damage. When threatened they also release saponins - compounds which destroy red blood cells. Together, these toxins can cause great pain to any animal (or human!) unfortunate enough to come into contact with it.

There are, however, some predators that eat this cocktail of starfish spines and toxic slime for dinner! The giant triton snail can hunt and devour crown-of-thorns starfish in a slow moving yet gruesome attack. Humphead maori wrasse, starry pufferfish and titan triggerfish also eat adult starfish. Shrimp, crabs and worms eat young starfish.

Starfish on the menu for more fish than previously thought

Recently, AIMS scientists discovered many more starfish predators than previously thought. The team collected poo and gut samples from reef fish species. Using eDNA technology, found many contained crown-of-thorns starfish DNA - evidence these fish are eating the starfish at some stage during their lifecycle.

Among the new-found predators were commercial and recreational fishing species such as coral trout, rock cods and tropical snappers. This discovery has led to further investigations of the influence of removing predators on starfish numbers and could provide another tool for managers to help control outbreaks.

Our research on starfish predators

Outbreaks are an ongoing complex problem

Since 1962, crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks have been a major source of coral loss on the Great Barrier Reef. A fourth outbreak is currently underway in the World-Heritage Area.

Outbreaks generally start offshore from Cairns or further to the north and take about a decade to spread south along the Reef. They can kill up to 90 per cent of the corals on affected reefs.

AIMS has been monitoring crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks and coral cover since the 1970s. These surveys show affected reefs do recover. However, increasing frequency of climate change related events such as marine heatwaves and coral bleaching and increased severity of cyclones means there is less time for recovery to occur.

What causes outbreaks?

Crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks are a complex ecological problem and have been studied on the Great Barrier Reef and around the world for decades.

There is general agreement that outbreaks have always occurred on the Great Barrier Reef. However, there is concern that human activities have altered the frequency of these outbreaks, adding to the increasing pressures on the Great Barrier Reef.

Several hypotheses regarding the cause of elevated outbreaks frequencies have been put forward and investigated, however it is likely that there are at least two factors involved:

- increased larval survival due to increased nutrients increasing phytoplankton levels – the food of crown-of-thorns starfish larvae.

- the removal of predators (fish and invertebrates), which reduces predation pressure on the starfish, particularly at the juvenile stage.

Outbreaks are a regional pressure and can be directly managed. Understanding the complexities of what causes of outbreaks is an ongoing area of research for AIMS and our collaborators.

Our research on causes of outbreaks

Star(fish) wars – controlling outbreaks

As pressures from climate change increase, the time between reef disturbances is becoming shorter leaving less time for the Reef to recover. This has led to an urgency to manage coral loss factors at a local or regional level. One way is to protect coral by controlling crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks through individual culling.

The approach to crown-of-thorns starfish culling is strategic.

Individual reefs are selected by managers to be protected from crown-of-thorns starfish based on several factors including their value to tourism, their importance for sharing corals with nearby reefs, and their role in spreading crown-of-thorns starfish. Divers kill the starfish by injecting them with bile salts or vinegar.

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority is responsible for the culling program. AIMS' Long-Term Monitoring Program starfish surveys assists with identifying reefs with high starfish numbers.

As well as developing new techniques to help identify outbreaks, AIMS scientists are developing innovative approaches to assist the control program. For example, crown-of-thorns starfish have a keen sense of smell, and baits are being developed to lure the starfish into aggregations for easy removal.