Unprecedented global collaboration across many disciplines is needed to overcome the research challenges of scaling up sexual production of corals, to help the world’s coral reefs combat the impacts of climate change and other threats.

This is the conclusion of a comprehensive review of research into the sexual reproduction of hard corals for reef restoration, led by the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS), recently published in the Marine Ecology Progress Series ‘Sexual production of corals for reef restoration in the Anthropocene’.

Despite being the ‘largest sex show on earth’, little was known about coral spawning on the Great Barrier Reef until researchers discovered mass spawning in 1983. Since then, marine scientists have studied how corals reproduce, seeking to better understand whether mass spawning can be harnessed to help reefs adapt more quickly to environmental changes.

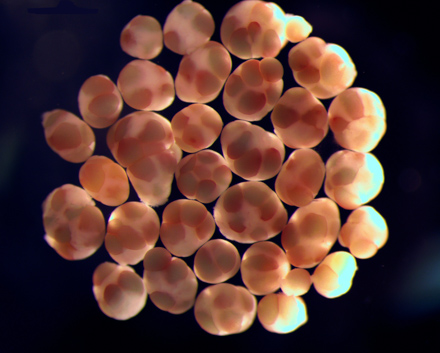

ln the review of more than 350 papers, AIMS coral reef restoration ecologist Dr Carly Randall and a team of leading marine researchers have synthesised the current knowledge of how corals sexually reproduce, from the development of gametes through the settlement of larvae. The review also considered the feasibility of using sexually-produced corals for larger-scale reef restoration and recovery.

“The knowledge gaps are in areas such as: controlling spawning cycles, capturing and characterising spawn slicks, overcoming the bottleneck of post-settlement survival, identifying factors that control sexual maturation and developing high-volume aquaculture production of corals,” Dr Randall said.

Coral reefs are experiencing frequent and severe disturbances, like marine heat waves, that cause coral bleaching and that are reducing global coral abundance and potentially overwhelming the natural capacity for reefs to recover.

Three large-scale bleaching events have occurred on the Great Barrier Reef over the past five years.

“We know that up to half of the world’s tropical corals have been lost in the past 50 years and more than one-third of hard coral species are now at increased risk of extinction,” Dr Randall said.

“Coral reefs provide significant ecosystem services, such as providing fish nurseries and protecting shorelines. Reef restoration and coral adaptation programs are being established worldwide as a conservation measure to minimise coral loss and enhance recovery.

“Most restoration efforts are focused on asexually-produced coral fragments which has inherent practical constraints on genetic diversity and the scale of restoration that can be achieved.”

Dr Randall said AIMS researchers were using sexually-produced corals in their studies, to include the potential for maintaining genetic diversity, and the potential for scaling-up coral adaptation projects.

“Overcoming the research challenges will require an unprecedented level of collaboration across nations, research groups and public and private sectors,” she said.

“Reef restoration researchers and practitioners will also need to draw on expertise from vastly different scientific disciplines such as microbiology, genetics, restoration ecology, aquaculture, materials science and engineering.

“However, no approach will be successful without swift and effective efforts to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions which must go hand-in-hand with reef restoration.”

AIMS is playing a key role in the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program, a consortium dedicated to creating an innovative toolkit of safe, acceptable interventions to helping the Reef resist, adapt to, and recover from the impacts of climate change.