AIMS’ marine biologists Dr Brett Taylor and Dr Mark Meekan have just returned from a 16-day research expedition with international leaders in their fields, to the postcard-perfect Chagos Islands.

Brett and Mark’s focus was not the white sands and palm trees, but below the azure waters of this pristine marine area, in a quest to finding answers to questions facing underwater environments around the world.

The area they visited is made up of archipelagos and more than 60 individual tropical islands in the Indian Ocean around 6000km off Western Australia in British Indian Ocean Territory.

In 2010, it became one of the largest Marine Protected Areas in the world, halting commercial fishing across 640,000km2 of the Indian Ocean and home to the world’s largest undamaged reef area.

Reef fish are six times more abundant there, than on any other reef in the Indian Ocean, with 821 species of fish and 310 species of coral. It is also one of the world’s least contaminated coastal areas.

Scientists believe it could be a global reference baseline for their research, and they suspect reef sharks play a fundamental role in maintaining healthy coral reefs. Joining them on the expedition were collaborating partners from Exeter University, Lancaster University, Stanford University, the Zoological Society of London, Imperial College London, Oxford University, and University of Victoria.

The Perth-based team of AIMS researchers used underwater cameras called `Baited Remote Underwater Video’ (BRUVS) to capture 95 hours of unique underwater footage at six islands and atolls in the area.

Dr Taylor said theirs was the most comprehensive survey of fish and reef sharks across the archipelago, and it would be compared with information being collected as part of an initiative called Global FinPrint.

The international initiative, supported by the Bertarelli Foundation brings together information to fill a critical information gap about the diminishing number of sharks and rays (elasmobranchs) around the world, into one place.

“We collected individual fish from eight species, including piscivorous and planktivorous snappers, herbivorous surgeonfish, and parrotfishes that feed on microbes from the reef matrix,” Dr Taylor said.

“The information we have gathered from these fish, can give us information about nutritional ecology of these species and their general responses to the 2015-2016 coral bleaching of reefs in those areas.

“The otoliths of long-lived species (snappers and surgeonfish) will be used to generate multi-decadal growth chronologies from which historical relationships with regional and basin-wide climate factors will be explored.

“For the shorter-lived parrotfishes, species-specific and general responses to the 2015-2016 coral bleaching will be explored, as the nutritional ecology of these species is intricately tied to reef substrates.

“Both approaches will inform our research on the productivity of fish populations under future climate change.

“We achieved all our primary objectives and now we have lots of work ahead in the laboratory back at AIMS research facility in Perth.”

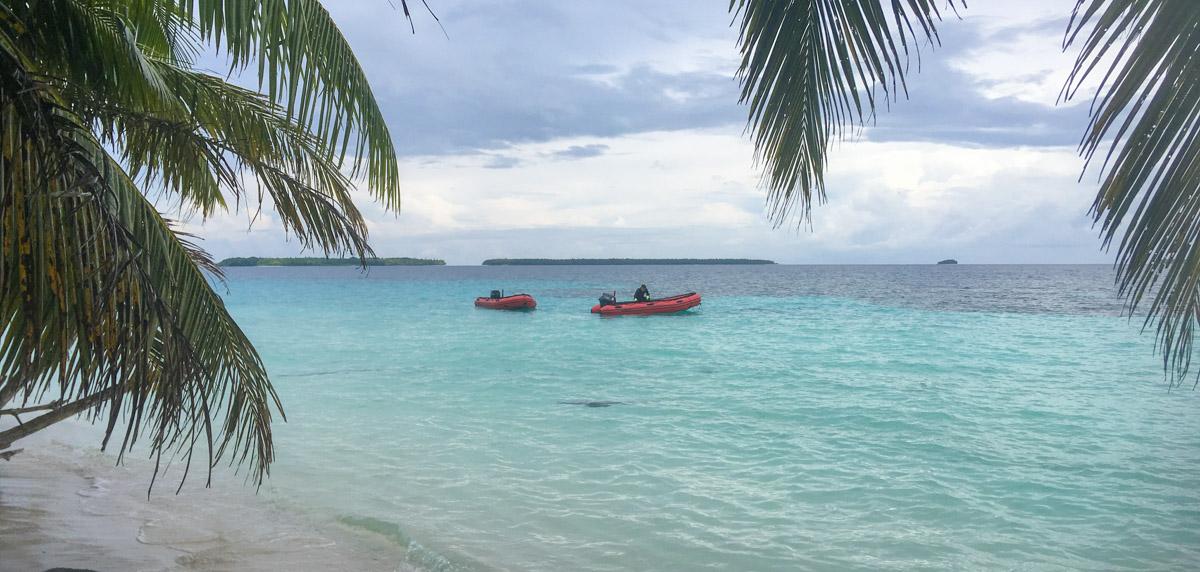

Feature image: Researchers prepare for a day in the field at Ile de la Passe, Chago Archipelgo