Scientists from James Cook University (JCU) and the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) have developed a new method to study microplastics swallowed by sea turtles.

The new technique will help assess whether microplastics are as dangerous to turtles as larger pieces of plastic.

Recent estimates suggest there are more than 5 trillion pieces of plastic debris floating in the world's oceans, a figure which doesn’t include waste on beaches or the seafloor.

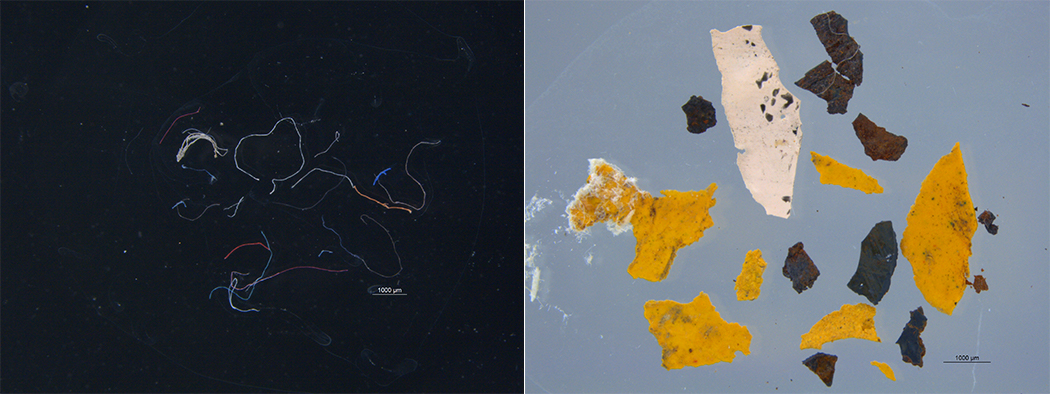

JCU’s Associate Professor Ellen Ariel said contamination of marine life by microplastics – pieces of plastic smaller than 5 mm in length - is poorly known and likely to be under-reported.

AIMS@JCU student Alexandra Caron, led the study. “As with bigger pieces of plastic, once swallowed, ingested microplastics may impact organisms physically as well as physiologically as they can leach associated plastic chemicals or other absorbed pollutants into the animal causing toxicity,” she said.

Sea turtles are at particular risk from plastics in the oceans because the seven species of marine turtles are already categorised as vulnerable to critically endangered.

“They look for things like jellyfish to eat, and a piece of soft floating plastic can appear very similar. Plastic debris can also become entangled among green turtle food sources such as seagrass leaves and seaweed. Turtles don’t have the capacity to regurgitate, so plastic particles tend to be swallowed and accumulate in the gut,” said Associate Professor Ariel.

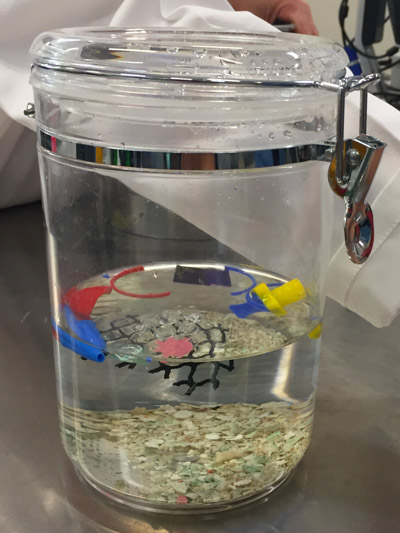

Under the supervision of AIMS marine chemist Dr. Cherie Motti the new method was applied. It involves a sequence of chemical treatments designed to separate out swallowed plastic particles from plant and animal food remains as well as any sediment the turtle has swallowed during feeding.

“We examined the gut of two green turtles using this new method, and even with this small sample set, found seven microplastics consisting of two plastic paint chips and five synthetic fabric particles. That’s in addition to also finding 4.5 m of nylon line and some soft plastic pieces entangled in the gut,” said Dr Motti.

“The new technique will increase our knowledge of the role plastic pollution plays in declining turtle health. But it has already highlighted the need for increased efforts in plastic pollution mitigation and reduction into the marine environment,” said JCU Professorial Research Fellow Dr Jon Brodie.

Media enquiries

Emma Chadwick

Communications Officer

Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville

Phone: +61 0412 181 919

Email: e.chadwick@aims.gov.au